Architecture for Humans

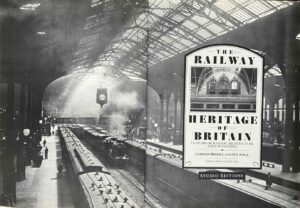

One of the glories of London is its array of historic railway terminuses. Liverpool Street (above), Paddington, St Pancras, King’s Cross, Waterloo, Victoria – these are one with St Paul’s, Westminster Abbey and the Tower of London as landmarks of national importance. All are listed buildings. Why would anyone want, or be able, to demolish them?

As reported in our news article Goodbye Liverpool Street, Network Rail intends to partially demolish Liverpool Street Station and build a 19-storey tower block over the train shed. As publisher of The Railway Heritage of Britain, I was invited to speak as an objector to the planning sub-committee of the City of London Corporation on 10th February. However, since objectors were allocated only 10 minutes to make their case, it made sense for only three or four people to speak. I therefore stepped aside in favour of others with greater experience of planning hearings. Had there been the time, this is what I would have said.

What So Many People Love About London

I have been interested in architecture since an early age. Brought up in a Kent village, I found going to London exciting. Being driven up through the suburbs of Peckham, Camberwell and New Cross, or stepping out of a train at Victoria Station, hearing the news vendors and hawkers crying their wares, seeing the great buildings, sensing the bustle of the metropolis was like being born again, swept away on a wave of urban energy.

As an undergraduate during the university vacations, I worked for a firm called Undergraduate Tours, taking tourists, mainly American, round St Paul’s, the Tower of London and Westminster Abbey, with maybe a glimpse of Buckingham Palace and the King’s Road or Carnaby Street thrown in if there was time.

One day, a lady said to me, ‘I want you to take me to Victoria Station.’ Seeing my hesitation, she explained she was a tour guide who wanted to create an alternative itinerary for her discerning clients. Having parked the car, we walked into the eastern train shed. Looking up at the glazed, two-bay arched roof with its striking radial struts, she drank in the bustle of the station and announced with satisfaction, ‘Yes, I will bring them here.’

Years later, after I set up Sheldrake Press, we planned to do a book called Cathedrals of Steam, about the historic railway terminuses, and I arranged to meet the Director – Environment at the British Railways Board, Bernard Kaukas, to ask if the railways might assist us.

‘I have another suggestion for you,’ he said. ‘Here’s the list of our Listed Buildings. Can you turn it into a book?’

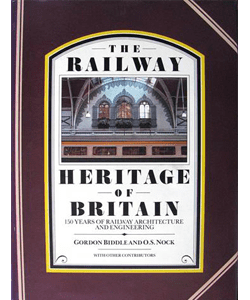

We made that into this:

The Railway Heritage of Britain was published on the initiative and with the full backing of the British Railways Board and contained a Foreword by the Chairman, Sir Peter Parker, acknowledging the importance of the railways’ built heritage. ‘Here is the unique architectural record of British achievement embodying the confident and pioneering spirit of the Railway Age,’ he wrote, ‘which, a century and more later, still forms the environment for a busy, working, modern railway.’ Bernard Kaukas contributed a four-page article setting out how British Rail aimed to improve the environment of its land and buildings and inviting the partnership of local people in securing the destiny of the historic railway station.

Bernard Kaukas had the idea that if you even just cleaned a Victorian building, people would realize its potential, so he had a section of the disused St Pancras Hotel washed. Years later, in 2011, Marriott Hotels finished the job, bringing the hotel back into use.

Admiring the grand staircase, with its fleur-de-lis wallpaper and painted, vaulted ceiling, Sir Simon Jenkins commented, ‘It’s beautiful.’

Historic Railway Terminuses

Beautiful is not a word one would instinctively pick to describe a transport hub. But is it not better to offer passengers a beautiful place to pass through rather than a functional one?

During the restoration of the St Pancras hotel, there was a planning application to increase the number of rooms by adding a modern box on one side, but it was rejected and Marriott Hotels were persuaded instead to commission a vaguely Gothic addition so as not to compromise the integrity of Sir George Gilbert Scott’s building.

Today, St Pancras is a destination. If I’m meeting anyone for a drink in that part of London, I will always take them to the Booking Office bar, a truly beautiful place to catch up.

The Threat of Destruction

Some of the world’s greatest stations have faced near disaster but escaped after public outcry. British Rail hoped to demolish St Pancras itself in 1966, but after a campaign led by Sir John Betjeman it was listed in 1967 and saved. In 1968 the Bauhaus architect Marcel Breuer came up with a plan to drive a skyscraper up through the middle of Grand Central Terminal in New York. It was rejected, and now you can enjoy the architecture as it was originally meant to be seen. It’s an eye-opener.

Pennsylvania Station was less fortunate. It was torn down in 1963. ‘Until the first blow fell,’ reported the New York Times, ‘no one was convinced that Penn Station really would be demolished, or that New York would permit this monumental act of vandalism against one of the largest and finest landmarks of Roman elegance.’ As Jonathan Glancey explains in Logomotive, our tribute to railway design in America, the Pennsylvania Railroad planned to sell air rights above a new underground concourse to property speculators. ‘It did,’ wrote Glancey, ‘and the result remains as grim as the day the new station opened in 1964. “One entered the city like a God,” said the American architectural historian Vincent Scully of the original 1910 station. “One scuttles in now like a rat.”’

In his book Britain’s 100 Best Railway Stations, Sir Simon Jenkins has a whole chapter on the Great Destruction, the period during the Beeching era when major landmarks were bulldozed one after another. That was the 1960s, when much of central London was scheduled for demolition, including even Covent Garden. In 1983, admittedly under pressure from the Secretary of State for the Environment, Michael Heseltine, the railways appeared to turn the corner when they commissioned The Railway Heritage of Britain. Sir Peter Parker declared in his Foreword that the railways were ‘delighted’ to follow his suggestion that their rich heritage of historic buildings should be available in published form.

How deep did the railways’ delight run?

Imagine my dismay when, in the late 1980s, I heard that the railways had their eyes set on redeveloping Liverpool Street Station. Bernard Kaukas advised me to meet Jane Priestman, his successor as Director Architecture, Design and Environment, and to plead the case for a sensitive treatment of the architecture. I took her to lunch at the Connaught Hotel and said my piece. She was polite but firm. The redevelopment plan would go ahead. But, she added, they would rebuild the spire that had been knocked off in the Blitz. I left feeling the spire was a sop, a token to distract attention from the invasive works that were planned.

In the event, the concourse was largely demolished and rebuilt. Admittedly the spire was put back on, albeit in a different place, but modern intrusions were inserted that obscured the trainshed and the inner face of the hotel. The result today is a mish-mash. The integrity of the building was compromised.

Architecture for Rats

The proposal now being considered is far worse. Another 20 years have gone by, but the railways are going back 60. They are reverting to the Great Destruction. It’s as bad as building a tower block through Grand Central. The proposed upper walkways and restaurants will obliterate the view of the trainshed. Passengers will be forced to scuttle through the concourse like sewer rats, as in the disastrously rebuilt Pennsylvania Station. Even worse is the 19-storey tower block which is proposed to rise above the station. This is as bad as Marcel Breuer’s proposal at Grand Central. It will totally overwhelm what survives of the original architecture and destroy the harmony of the surrounding conservation zone.

‘Make no little plans,’ wrote Daniel Burnham, architect of magnificent Union Station in Washington D. C. ‘They have no magic to stir men’s blood.’

The engineer and architect of Liverpool Street Station, Edward Wilson and W. N. Ashbee, chose magic. As Gordon Biddle wrote in The Railway Heritage of Britain, ‘the effect of the curved ties, double rows of slender columns with deep filigree brackets and the airy, pointed aisles and transepts is like some great Gothic iron-and-glass cathedral’.

All this will be obscured in the works now being proposed by Network Rail.

Buildings Held in Trust

Would anyone build a tower block over St Paul’s Cathedral or the Tower of London? So why do it at Liverpool Street? What custodian of the nation’s built heritage would even contemplate such a plan? Since the Great Destruction, the railways have presided over the halting, piecemeal but ultimately successful restoration of terminuses such as St Pancras and Paddington and other stations large and small. They seemed to have accepted that the tide had turned against demolition. As successors to British Rail and Railtrack, you would expect Network Rail to honour the commitment to the railway heritage declared in the clearest terms by Sir Peter Parker and Bernard Kaukas. What contusion of the mind, one has to ask, has brought them to renege?

Planning on the Wrong Premise

Last autumn I took my grandchildren up the dome of St Paul’s. Looking out from the cupola, what did we see? Boring buildings. The Blitz destroyed much, but post-war developers have destroyed far more. I realized we were standing on one of the few buildings still worth looking at. Since Bauhaus, architecture has been degraded by the idea that form follows function, and we are all the poorer for it.

The fundamental error with the proposed redevelopment of Liverpool Street Station is that it is based on the wrong premise: that function is king. It overlooks the fact, accepted by British Rail in the 1980s, that the railway heritage is a responsibility, a trust to be honoured on behalf of the nation. It is also a business asset. A landmark station is something tourists will want to see and passengers appreciate. It will lift their spirits as they go about their daily business, stir their blood.

So, dear railway bosses, successors to Sir Peter Parker and Bernard Kaukas, Look, Listen, Stop and Think. Don’t treat your passengers like rats. Withdraw this retrograde plan and start with form: make the most of the splendid architecture you have, and work from there.